Viral vector-based vaccine; DNA-based vaccine; RNA based vaccine- A landscape for vaccine technology against infectious disease, COVID-19 and tumor

SOCAIL MEDIA

Table of Contents

Abstract

The vaccine helps to provoke the immune system and is an efficacious means for disease prevention and treatment. At this particular time of the COVID-19 outbreak, the vaccine for COVID-19 is urgently needed to save tens of thousands of people’s lives. Here we give some basic information on vaccine classification, generation, and application, and make a brief review on the current status of COVID-19 vaccine and tumor vaccine development both in the clinical trial stage and pre-clinical stage.

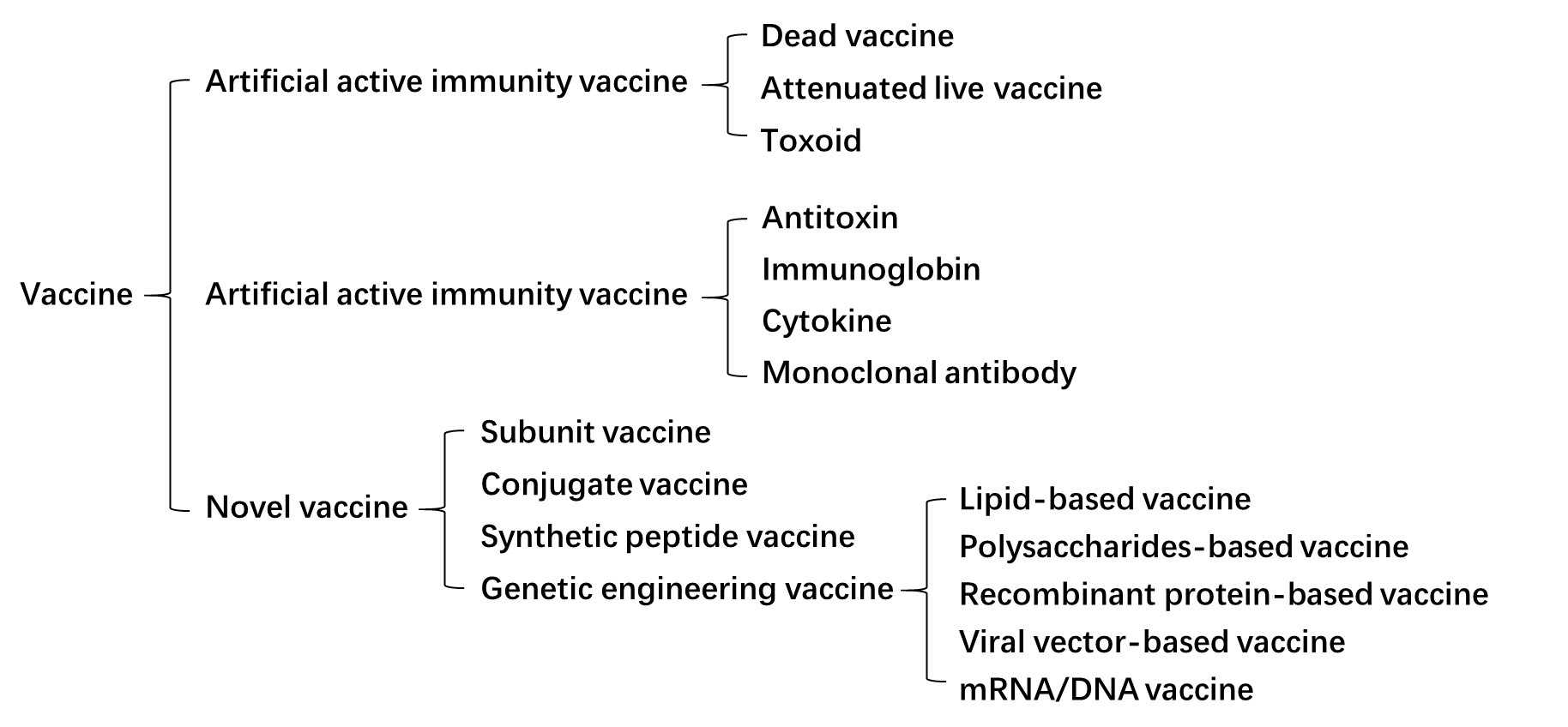

1. Landscape of vaccines

A vaccine is any substance produced from various pathogenic microorganisms and can spur the body’s immune system to generate antibodies for the prevention, diagnosis, or treatment of diseases when given to the body, including artificial active immunity vaccine, artificial passive immunity vaccine and novel vaccine (Fig. 1). Traditionally, the artificial active immunity vaccines can be divided into three categories: dead vaccines, live vaccines, and toxoid (Fig. 1). Dead vaccines are dead parts or wholes of germ cells, once injected into people or animals, they can trigger mild immune responses, containing pertussis vaccine, typhoid vaccine, meningococcal vaccine, cholera vaccine, etc.; while live vaccines are living parts or all of germ cells, most of them are attenuated to reduce the risk but also provide immunity for the body, such as BCG vaccine, polio vaccine, measles vaccine, plague vaccine, etc.; toxoid is a kind of extracellular toxin treated by formaldehyde, which loses the toxicity but retains the immunogenicity, such as diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid. Considering the long-term required for immune system activation using artificial active immunity, the artificial passive immunity vaccine is designed for rapid disease treatment or emergency prevention, including antitoxin, immunoglobin, cytokine, and monoclonal antibodies.

Besides these two kinds of immunity vaccines, some novel vaccines have been developed or created, such as subunit vaccine, conjugate vaccine, synthetic peptide vaccine, and genetic engineering vaccine (recombinant protein-based vaccines, lipid-based vaccines, polysaccharides-based vaccines, viral vector-based vaccines, and mRNA/DNA vaccines, etc.). However, some of them, such as lipid-based vaccines and polysaccharides-based vaccines, only result in poor immunogenicity. The reasons might be that some antigen structures with adjuvant activity are discarded during vaccine preparation, or some vaccines can only trigger one kind of immune responses, such as cell-mediated or humoral immune responses. Among them, viral vector-based vaccines, and mRNA/DNA vaccines can provoke both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses, which are promising candidates with great potential in the future.

2. Viral vector-based vaccines

Viral vector-based vaccines are vaccines that can deliver specific antigen gene to target cells based on the infection ability of viruses, produce antigens via the nutrition substances in host cells, and then provoke immune responses with the newly synthesized antigens. Compared with the traditional vaccines, viral vector vaccines have a great number of advantages: ①highly efficient in gene transduction; ② mediate specific gene delivery to target cells; ③induce of both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses; ④ better efficacy and safety;⑤ just need low administration dose; ⑥ easy to be applied into large-scale manufacturing; ⑦ possessing widespread potential target diseases, ranging from infectious diseases to cancers. As well, some drawbacks also have been discovered: ① several kinds of vectors mediate gene integration into host genome, which may lead to cancer; ② some hosts may be exposed to antigens prior to the vaccine administration, which may result in the production of neutralizing antibodies (pre-existing immunity) and thus reduce the vaccine efficacy [1].

To date, numerous kinds of viral vectors have been introduced to produce vaccines, such as adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors (Fig. 2A), adenoviral vectors (Fig. 2B) and lentiviral vectors (Fig. 2C) [2]. Different kinds of viral vectors have their advantages and drawbacks, which are summarized in Table 1.

| Viral vectors | Lentivirus | Adenovirus | AAV |

| Genome | ss RNA | ds DNA | ss DNA |

| Integration | Yes | No | No |

| Packaging Capacity | 4kb | 5.5kb | 2kb |

| Time to peak expression | 72h | 36h-72h | Cell: 7 days; Animals: 2 weeks |

| Sustainable time | Stable expression | Transient expression | > 6 months |

| Cell Type | Most Dividing/Non-Dividing Cells | Most Dividing/Non-Dividing Cells | Most Dividing/Non-Dividing Cells |

| Titer | 10^8 TU/ml | 10^11 PFU/ml | 10^12 vg/ml |

| Animal experiment | Low efficiency | Lowest efficiency | Most suitable |

| Immune Response | Medium | High | mild |

1) AAV vector-based vaccines

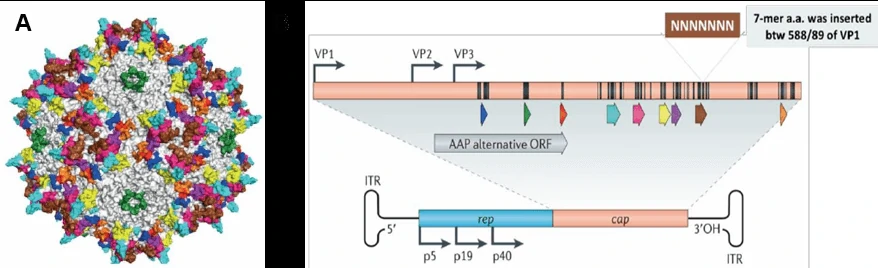

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) is a small single strand DNA virus, member of human parvovirus [3, 4], approximately 25nm in diameter and encapsidates a single-stranded DNA genome of 4.7 kilobases (Fig. 3A). The genome consists of two large open reading frames (ORFs) flanked by 145bp inverted terminal repeats (ITR), which are the only cis-acting elements required for AAV genome replication and AAV packaging. The left ORF encodes four replication proteins, Rep40, Rep52, Rep68, and Rep78, in charge of site-specific integration, as well as regulation of AAV capsid formation initiation within the AAV genome, while the right ORF encodes the viral structural proteins, VP1, VP2, and VP3, which interact together to assemble into icosahedral virion shells comprising 60 subunits each (Fig. 3B).

Principle

Principle of AAV entry into cells

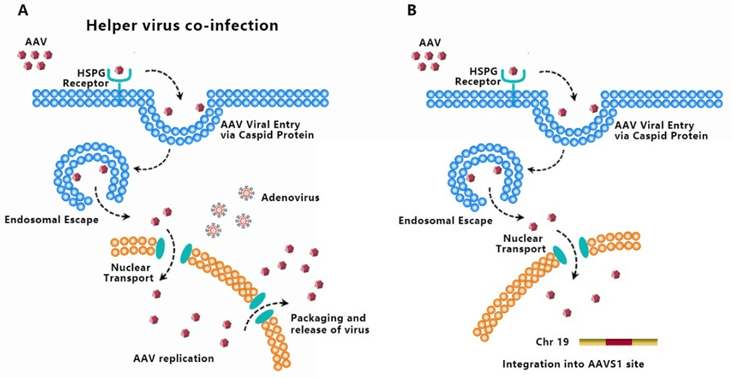

AAV transduces cells through several stages: ① viral binding to cell surface receptor/coreceptor, ② endocytosis of the virus, ③ intracellular trafficking of the virus through the endosomal compartment, ④ endosomal escape of the virus, ⑤ intracellular trafficking of the virus to the nucleus and nuclear import, ⑥ virion uncoating, ⑦ viral genome conversion from a single-stranded to a double-stranded genome capable of expressing an encoded gene [5-7]. Since AAV has no ability to encode polymerases, AAV is dependent upon cellular polymerase activity to replicate its own genome [8]. The presence of a helper virus such as adenovirus is indispensable for wild-type AAV to facilitate gene expression and replication (Fig. 4A). Without helper virus, expression of Rep68/Rep78 would be restricted owing to Ying Yang 1 (YY1) repression of the P5 promoter, leading to inhibition of AAV genome replication and gene expression, and initiation of AAV chromosome integration (Fig. 4B) [9]. AAV establishes latency by undergoing specifically integration into a genome site, termed as the adeno-associated virus integration site 1 (AAVS1), a 4kb region on chromosome 19 (q13.4).

Immune responses induced by AAV-based vaccine

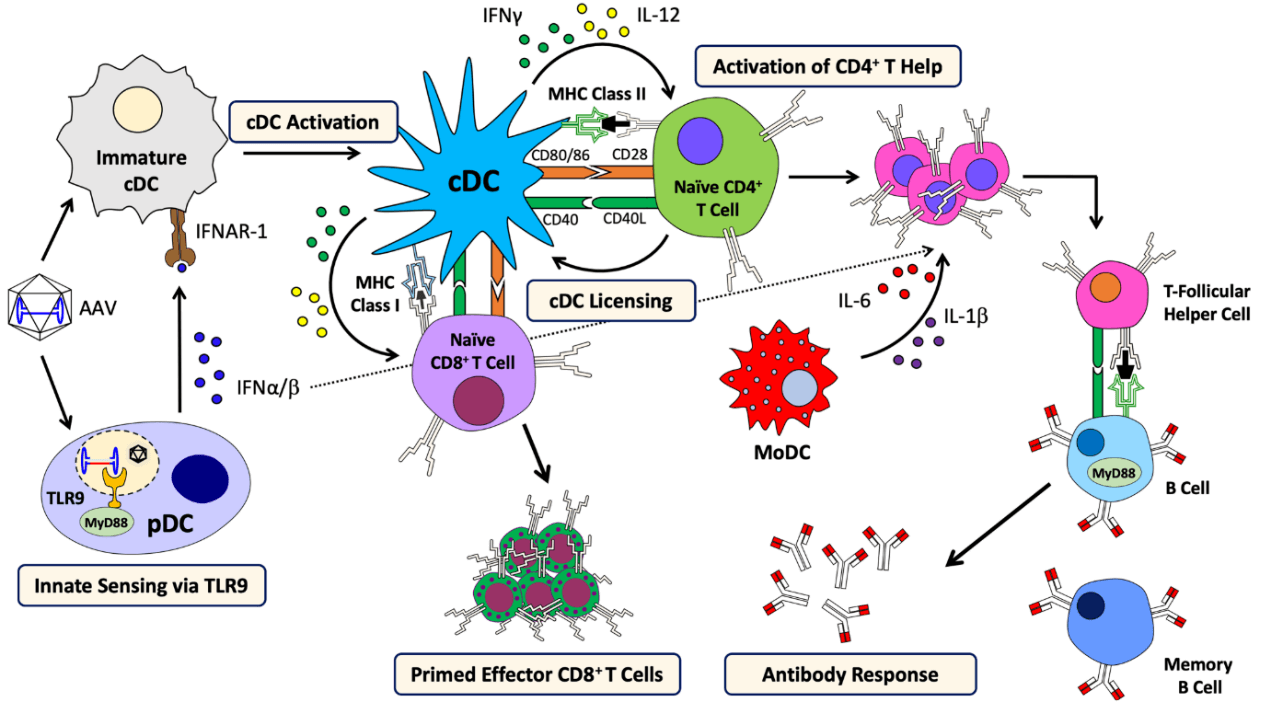

During the entry of AAV into host cells, AAV virions may uncoat and release their genomes into the endosome, and be recognized by toll like receptor 9 (TLR9) of plasmacytoid dendritic cell (pDC) to provoke innate immune response and produce Interferon (IFN) α/β [10]. This process is dependent on MyD88 signaling, but not the form of transgene or capsid serotype [10]. Besides TLR9, TLR2 dependent cytokine expression was also observed in Kupffer cells [11]. Moreover, some AAV virions are degraded and processed into peptides within proteasomes, and then presented by MHC I of antigen presenting cells (APCs), such as conventional dendritic cells (cDCs), which can be targeted by capsid-specific CD8+ T cells to lyse virally infected cells [12]. In addition to IFNα/β, CD40-CD40L co-stimulation by CD4+ T helper cells, is required for cross-priming of CD8+ T cells against AAV capsid [13]. CD4+ T helper cells is also indispensable to generate memory responses and stimulate B cells to produce antibody against AAV capsid, which is dependent on MyD88 signaling [14].

Application

AAV serotypes

Over the past decades, numerous AAV serotypes have been identified with variable tropism. To date, 12 AAV serotypes and over 100 AAV variants have been isolated from adenovirus stocks or from human/nonhuman primate tissues. Among them, AAV2, AAV3, AAV5, AAV6 were discovered in human cells, while AAV1, AAV4, AAV7, AAV8, AAV9, AAV10 (AAVrh10), AAV11, AAV12 in nonhuman primate samples [16]. Different serotypes have different tissue tropism, which are summarized in Table 2.

| AAV Serotype | Tissue tropism | |||||||

| CNS | Retina | Lung | Liver | Pancreas | Kidney | Heart | Muscle | |

| AAV1 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| AAV2 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| AAV3 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| AAV4 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| AAV5 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| AAV6 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| AAV7 | √ | √ | ||||||

| AAV8 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| AAV9 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| AAV-DJ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| AAV-DJ/8 | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| AAV-Rh10 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| AAV-retro | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| AAV-PHP.B | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| AAV8-PHP.eB | √ | √ | ||||||

| AAV-PHP.S | √ | √ | √ | |||||

Recombinant AAV

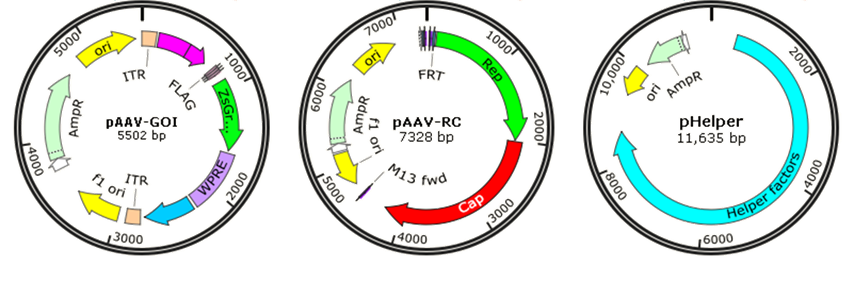

Though wild-type AAV is not associated with human disease, it is naturally defective and requiring helper adenovirus or herpes simplex virus (HSV) coinfection for AAV replication, so recombinant AAV (rAAV) has been developed for gene therapy or vaccines by replacing the viral genome with gene of interest (GOI) to reduce the risk. Traditionally, rAAV vectors used in clinical trials were prepared with a plasmid containing the therapeutic gene flanked by AAV-inverted terminal repeats (ITRs), co-transfected with AAV packaging plasmid pAAV-RC (AAV replication and AAV capsid) and pHelper (AAV helper plasmid) (Fig. 6). The adenovirus helper factors, such as E1A, E1B, E2A, E4 ORF6 and VA RNAs, would be provided by the third helper plasmid. Due to the deletion of Rep and Cap coding regions between the ITRs, rAAV vectors cannot integrate into the genome of host cells, just persist in an episomal form, which significantly reduced their tumorigenicity.

AAV-based gene therapy

To date, more than 244 clinical trials have been carried out using AAV vectors for gene delivery [17], and promising gene therapy outcomes have been achieved from Phase 1, Phase 2 and Phase 3 trials for a great number of diseases, including lipoprotein lipase deficiency (LPLD) [18], spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) [19], retinal dystrophy [20, 21], cystic fibrosis [22, 23], Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy [24], Hemophilia [25], congestive heart failure [26], Parkinson’s disease [27] and Rheumatoid Arthritis [28, 29].

AAV-based vaccine development

But, as a viral vector used for vaccine production, AAV only induces mild immune responses, which is not enough for vaccine to provoke the immune system in host. Several animal studies show that AAV vector-based vaccines can be used to defense HIV-1 [30-32], influenza [33], and papillomavirus [34] and have great potentials in clinical applications. However, AAV vector-based vaccines are rarely applied in clinical trials. Some of the examples are listed in the following Table 3. There are two reasons: ① AAV vectors only cause mild humoral and cellular immunity; ② infectious vaccines transduce a large population of people ranging from children and adolescents, and more safety risks need to be considered. Therefore, compared to the gene therapy with AAV vectors, there is a long way for the clinical applications of AAV vector-based vaccines.

| Disease | Vaccine component | Status | Clinical trials |

| HIV | AAV2 | Phase I | NCT00482027 |

| HIV | AAV2 | Phase II | NCT00888446 |

| HIV | AAV8 | Phase I | NCT03374202 |

| HIV | AAV1 | Phase I | NCT01937455 |

| Stage IV gastric cancer | AAV-DC-CTL | Phase I | NCT01637805 |

| Stage IV gastric cancer | AAV-DC-CTL | Phase I | NCT02496273 |

Advantages and disadvantage

AAV viral vector has been developed into a very attractive candidate for gene delivery due to various advantages: ① superior biosafety rating of recombinant AAV after removing most AAV genome elements; ② stable physical properties; ③ broad range of infectivity, AAV has the ability to infect both dividing and quiescent cells in vivo; ④ mediate long term and stable gene expression.

However, there are also some drawbacks for AAV to be used as vaccine vector: ① limited cloning capacity (less than 4.7kb) of the vector, which restricts its use in gene delivery of large genes [35]; ② only inducing mild immunity, restraining the vaccine development; ③ pre-existing immunity and neutralizing antibodies (NAB) against AAV vectors may attenuate the effect of AAV-based gene therapy or vaccines [36].

Optimization strategies

To improve the efficacy of AAV vector for vaccine development, several strategies are adopted: ① assemble and recombine proteins between different viruses, which can produce hybrid rAAVs, such as transcapsidation, which is a process involving the packaging of the ITR from one AAV serotype into the capsid of another serotype, which may determine the tissue tropism of hybrids. ② Recombine, redesign, or introduce random mutations into the capsid protein of AAV by different methods to artificially increase the variance of AAV serotypes, and then screen the appropriate AAV serotypes, including rational design AAV capsid [37], AAV directed evolution [38], point mutation [39], peptide display [40], and DNA shuffling [41]. ③ In combination with other kinds of vaccines.

GeneMedi holds the expertise at AAV production, you can find more information and protocols about AAV on this website: https://www.genemedi.com/i/aav-packaging.

2) Adenoviral vector-based vaccines

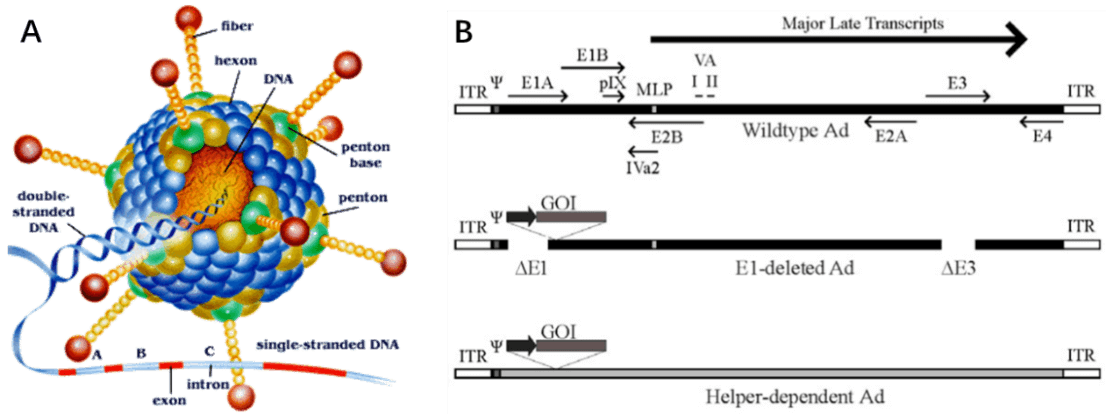

Adenovirus (AdV) is a member of the family Adenoviridae, whose name derives from their initial isolation from human adenoids in 1953 [42]. It is a medium sized (90-100nm) and non-enveloped virus with an icosahedral nucleocapsid containing a 36kb double stranded DNA genome (Fig. 7A). Hexon and penton structures form the capsid of AdV, and fiber protein mediates the binding of the virion to the cell surface and is a major determinant of viral tropism. Adenovirus transcription is a two-phase event, early and late, occurring before and after viral DNA replication, respectively (Figure. 7B). The early transcribed regions are E1A, E1B, E2A, E2B, E3, and E4, involved in viral transcription regulation, viral DNA replication, and the suppression of host immune response during infection. The late transcribed genes are L1-L5, encoding viral capsid components (Fig. 7B).

Principle

Principle of AdV entry into cells

For most serotypes, adenovirus infection is mediated by the high-affinity binding of the fiber-knob region to a receptor of target cell, named as the coxsackie-Ad receptor (CAR), which mainly determines the viral tropism [44]. Upon attachment, interaction between the penton-base Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) and cellular αv integrins, which can stimulate actin polymerization, leads to internalisation of the virus into the endosome. Then the endosome acidifies, resulting in disassociation of capsid proteins and transportation of viral DNA into nucleus. Without integration into host genome, adenovirus genome remains in an episomal state, which guarantees the low risk of mutation (Fig. 8). Life cycle of adenovirus is separated by DNA replication process into two distinct phases: the early and late, occurring before and after viral DNA replication, respectively. After the synthesis of viral genome and capsid, they are assembled into viral products, releasing out of cell, and the infected cell starts lysis [45]. To prevent infected cell lysis, recombinant replication deficiency virus has been developed as a gene delivery tool to replace wild-type adenovirus (recombinant AdV in “application” part). Once packaged into a E1-complementing cell line, which provides the E1 products in trans, such as QBI 293A Cells, recombinant viral will be easily propagated.

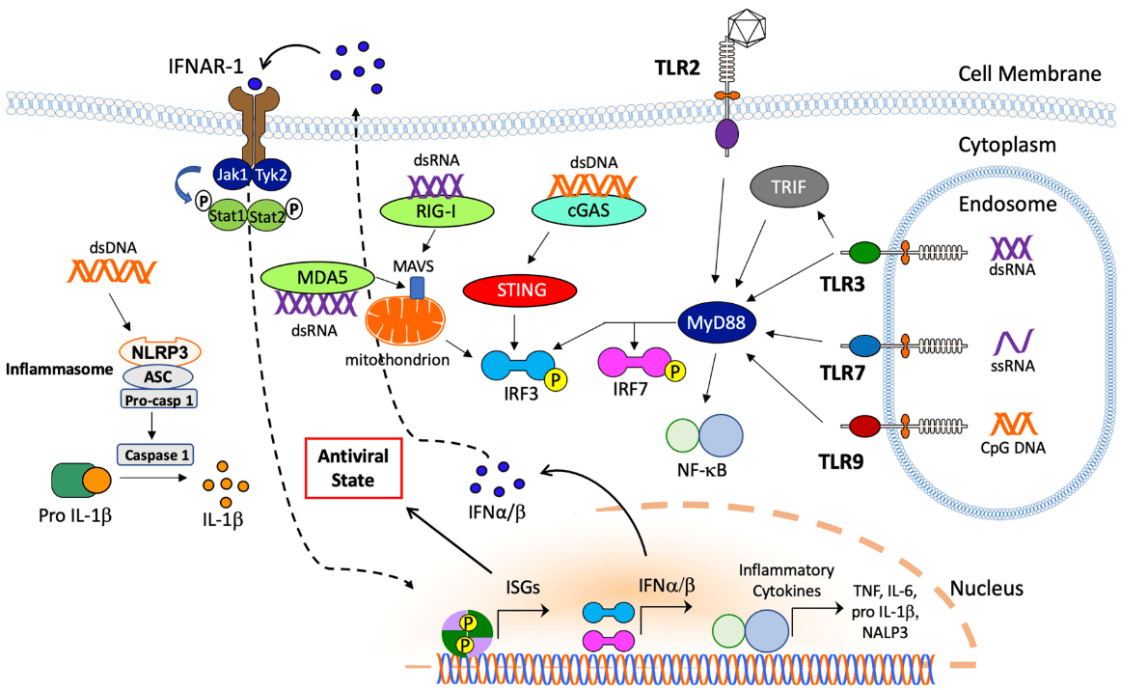

Immune responses induced by AdV

The entry of AdV into human body stimulates a wide spectrum of innate cellular responses, which might last a few minutes to hours and result in blood pressure changes, thrombocytopenia, inflammation, and fever [47]. AdV vector in blood activates vascular endothelial cells to release von Willebrand factor (vWF), induces platelets to expose the adhesion molecule P-selectin, and promotes the formation of platelet-leukocyte, ultimately leading to thrombocytopenia and bleeding [48]. Additionally, the hexon component of AdV capsid can bind to coagulation factor X (FX) to activate TLR4 on the surface of splenic macrophages and thereby stimulate NF-κB dependent activation of IL-1β, which may help recruit polymorphonuclear leukocytes to the marginal zone of the spleen and clear virus from the spleen rapidly [49, 50]. Besides binding to coagulation proteins, AdV in blood vessel can also bind to component C3 and natural [51-55]. Antibody-AdV complexes can provoke inflammatory cytokine and chemokine responses in macrophages via the intracellular antibody receptor TRIM21 [56-59].

In addition to innate immune responses in circulation, AdV virions can also be trapped by splenic macrophages (MFs) of the MARCO subset via the binding of fiber knob of the capsid to integrin b3 receptor [60]. This binding process leads to the release of IL-1α and activation of IL-1 receptor, promoting chemokines production and attracting other innate immune cells to kill AdV infected MFs [61]. AdV also activates the NLRP3 inflammasome to recruit proinflammatory caspases and promote IL-1β expression, thereby resulting in necrotic cell death [62]. Cytosolic sensing of AdV DNA via cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) binds to stimulator of interferon genes (STING) to promote IRF3 phosphorylation to produce type I IFN [63, 64]. Moreover, AdV DNA is also sensed by the endosomal receptor TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9 to activate MyD88 signaling pathway. Nuclear sensing mechanisms of AdV DNA can also promote or inhibit immunity [65, 66]. These pathways cooperate to regulate the immune responses triggered by AdV vectors.

In the meantime, AdV also provoke highly effective adaptive immune responses, and the mechanism is similar to that of AAV. But contrary to AAV, AdV triggers a particularly strong CD8+ T cell responses, which is facilitated by potent induction of Th1 immunity [67]. Due to the induction of extremely strong immune responses, AdV vectors are a prerequisite vector for vaccine development.

Application

Recombinant AdV

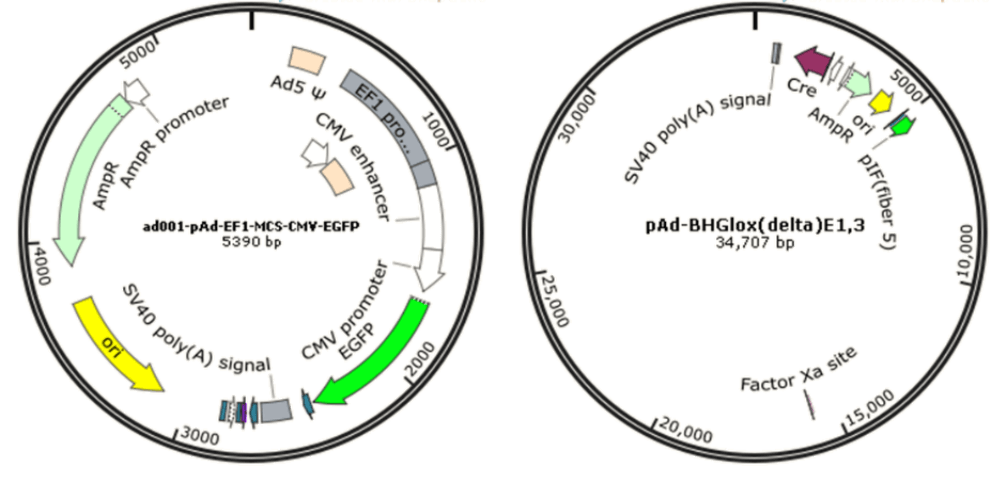

Since wild-type adenovirus is associated with a wide range of illnesses and enlists a variety of immune responses, so recombinant replication deficiency virus has been an attractive vector for gene therapy [68]. To date, there have been many different generations of adenovirus vectors, differing in the extent to which the genome from wild-type adenovirus is attenuated. Based on human adenovirus type 5 (Ad5), recombinant adenovirus (Ad) a replication-defective adenoviral vector system, is widely used for gene delivery in most dividing and non-dividing cells based on its advantages in high transduction efficiency, high level of transgene expression, and broad range of viral tropism [69]. Traditionally, recombinant adenovirus vectors used in gene delivery were prepared with a plasmid containing the transgene flanked by inverted terminal repeats (ITRs), co-transfected with packaging plasmid pAd-BHGlox(delta)E1,3 (Fig. 10). Once packaged into a E1-complementing cell line, such as QBI 293A cells, recombinant viral will be easily propagated.

AdV vector-based gene therapy

To date, more than 535 clinical trials have been carried out using adenovirus vectors for gene delivery [17], and promising gene therapy outcomes from recombinant adenovirus have been achieved from clinical trials for a great number of diseases, especially for cancer treatment, such as prostate cancer [70], chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) [71], non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [72], melanoma [73], renal cell carcinoma [74].

AdV vector-based vaccine development

As a viral vector used for vaccine production, AdV induces strong immune responses and show better superiority than other viral vectors. In clinical trials, AdV vector-based vaccines have been used to prevent HIV-1 [75, 76], influenza [77], tuberculosis [78], and solid tumors [79]. Some of examples in clinical trials are listed in Table 4 [80]. However, there are also some reports with discouraging outcomes. For example, Ad5 vector with neutralizing antiserum against HIV contrarily significantly facilitated HIV infection besides the enhanced immune responses [81]. The pre-existing anti-AdV immunity against Ad5 is proved to be another limiting factor for the clinical application of Ad vector-based vaccines [82]. Therefore, although AdV vector exhibits some advantages over AAV vector in vaccine production, there are also some safety hazards and pre-existing anti-AdV immune responses needed for further exploration.

| Target | Disease | Status | Clinical trials |

| Infectious diseases | HIV | Phase I/II | NCT00865566; NCT00413725 |

| HIV | Phase II | NCT00415649; NCT00125970; NCT00498056; NCT00123968; NCT00095576; NCT00080106; NCT00350623; NCT01159990 | |

| Malaria | Phase I/II | NCT00870987; NCT00392015; NCT01366534; NCT01397227 | |

| Malaria | Phase II | NCT01666925; NCT01658696; NCT00890760 | |

| Hepatitis C virus | Phase I/II | NCT02309086 | |

| Ebola virus | Phase I/II | NCT02289027 | |

| Ebola virus | Phase II | NCT02344407 | |

| Tuberculosis | Phase I/II | NCT01017536 | |

| Tuberculosis | Phase II | NCT01198366 | |

| Rotavirus | Phase III | NCT01305109 | |

| Cancer | Colon/breast/lung/head/neck/renal | Phase I/II | NCT00049218; NCT00669136; NCT00880464; NCT00776295; NCT00082641; NCT00093548; NCT01042535; NCT00617409 |

| Colon/breast/lung/head/neck/renal | Phase II | NCT00589186; NCT01147965; NCT01924156 | |

| Prostate | Phase II | NCT00583752; NCT00583024 | |

| Lymphoma | Phase II | NCT00849524; NCT00942409 | |

| Solid tumor/tissue sarcoma | Phase I/II | NCT02285816; NCT01898663 | |

| Leukemia/glioblastoma | Phase II | NCT01773395; NCT00589875 | |

| Melanoma | Phase I/II | NCT00039325; NCT00704938; NCT00010309 | |

| Melanoma | Phase II | NCT00004025 |

Advantages and disadvantage

There are many advantages of AdV as a vector for clinical trials: ① well tolerated with no obvious influences on the cell viability after infection; ② great packaging capacity (up to 8kb); ③ broad range of infectivity, from dividing cells to non-dividing cells; ④ high infection efficiency; ⑤ no integration ability into the host genome, remaining epichromosomal in host cells, thus no oncogenicity; ⑥ inducing a wide variety of immune responses, including humoral and cellular immunity. These advantages make AdV as an excellent vector for vaccine development.

Although adenovirus benefits a great deal of disease prevention, it does present some drawbacks: ① AdV-mediated gene delivery may not sustain for long time, just transient expression; ② pre-existing immunity and neutralizing antibodies (NAB) against AdV vectors might attenuate the preventive effects of AdV vector-based vaccines [83]; ③ despite reduced overall virulence, recombinant Ad5-based vectors exhibit a strong tropism for liver parenchymal cells due to the high expression level of CAR in hepatocytes, which increases hepatotoxicity and limits the clinical use of AdV vectors [84].

Optimization

Several measures were taken to improve the efficacy of AdV vector for vaccine development: ① modify the fiber protein to alter the tissue tropism and decrease the hepatic toxicity [85]; ② reduce viral vector-derived immune responses by changing virus gene expression, such as deleting E1 and E4 gene of AdV [86]; ③ modify the fiber protein to enhance the transduction of T cells and dendritic cells [87].

Genemedi got a rich experience in adenovirus packaging, you could find more information on https://www.genemedi.com/i/adenovirus-packaging.

3) Lentiviral vector-based vaccines

Lentivirus (lente-, Latin for “slow”) is a genus of retroviruses, medium sized (80-100nm) and enveloped, slightly pleomorphic, spherical with an isometric nucleocapsid containing two copies of positive-sense ssRNA genome (Fig. 11A). Most lentiviral vectors are based on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), which causes AIDS, a chronic and deadly diseases in human or other mammalian species [88]. Its DNA genome, transcribed from HIV-1 ssRNA, is approximately 9.7 kb and contains 9 open reading frames (ORFs), which are flanked by 5’ and 3’ long terminal repeats (LTRs), which are required for HIV-1 life cycle, such as reverse transcription, integration, and gene expression (Fig. 11B).

Principle

Principle of lentivirus entry into cells

HIV-1 virus enters host cells through binding to the CD4 receptor or a coreceptor (CCR5 or CXCR4) with gp120 protein, thereby anchoring itself onto host cell surface, allowing fusion between the cellular and viral membranes. After entry into the cell, the viral nucleoprotein together with the contents, i.e. the genomic ssRNA, is released into cytoplasm. Then, utilizing the cellular nucleotides as the building blocks, double-stranded DNA is generated from the virus genome ssRNA directed by the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT) in a nucleoprotein complex termed the RTC. Together with other viral proteins, the newly synthesized DNA constitutes an integration-competent nucleoprotein complex, migrating into host cell nucleus and mediating integration of viral DNA into host chromatin. Integrated viral DNA, named as provirus, becomes part of host genome and serves as a transcription template for the synthesis of viral mRNA and genomic RNA. Following the synthesis of viral genomes and proteins, the viral components are assembled together to produce new virions, the virus particles then bud out of host cell and undergo a maturation step to generate infectious HIV-1 (Fig. 12) [90].

Immune responses induced by lentivirus

Compared to HIV-1 virus, lentiviral vectors elicit weaker IFNα responses from pDC. SsRNA molecules of lentiviral vector in endosomes can be sensed by TLR7, while the reverse-transcribed CpG DNA is sensed by TLR9. TLR7 and TLR9 both contribute to induction of T1 IFN [91, 92] and regulation by mTOR pathway [93]. In addition to innate immune responses, lentiviral vector efficiently transduces APCs, such as MFs and DCs, which significantly facilitates the immune responses against transgene antigen. It was reported that transgene antigen expression in pDCs mainly drives immune responses, while antigen expression in myeloid cells may not obviously provoke immune responses [94, 95]. Furthermore, cell-derived MHC I molecules also helps trigger T cellular immune responses.

Application

Recombinant lentiviral vector

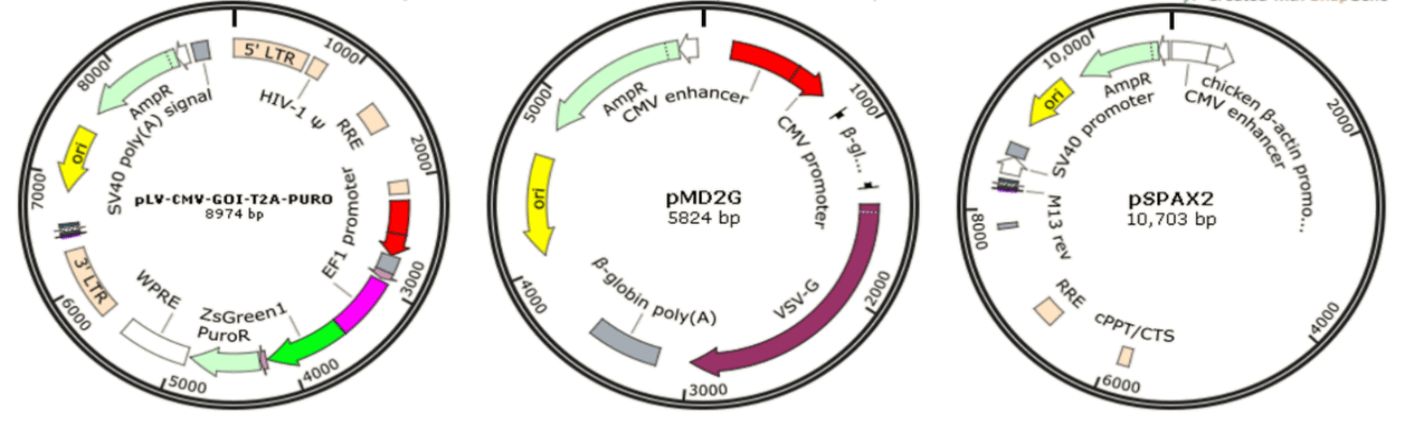

Since wild-type HIV-1-based lentivirus is associated with destruction of host immune system, especially CD4+ helper T lymphocytes, multiple generations of lentivirus vectors have been designed with enhanced safety features and as attractive vectors for gene therapy and vaccine production. To date, there have been several generations of HIV-1-based lentivirus vectors by deleting the HIV viral envelope and some of the regulatory genes not required during vector production [89]. The recombinant lentiviral vectors in GeneMedi are prepared based on three plasmids co-transfection system: vector plasmid pLV-CMV-MCS-T2A-PURO, envelope expressing plasmid pMD2G, and packaging plasmid pSPAX2 (Fig. 14). Once packaged into 293T, recombinant lentiviral vectors will be easily produced.

Lentiviral vector-based gene therapy

To date, more than 236 clinical trials have been carried out using lentivirus vectors for gene delivery [17]. For instance, lentiviral vector-based gene delivery into CD34+ HSCs has been used as an alternative in clinical trials and proved to be effective in treatment of several diseases [96], including β-thalassemia [97], X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) [98], metachromatic leukodystrophy [99, 100], and Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome [101].

Lentiviral vector-based vaccine development

In addition, as a viral vector used for vaccine production, lentiviral vectors can transduce antigen-presenting cells with high efficiency, such as dendritic cells [102], which provides some priority to lentiviral vector-based vaccines. Animal studies demonstrate that lentiviral vector-based vaccines can provoke both CD8+ T-cells and CD4+ T-cell responses and show great defense effects against melanoma by targeting NY-ESO-1 antigen [102, 103], or Melan-A/MART-1 antigen [104]. Besides, lentiviral vector-based HIV vaccines induce Gag-specific T-cell responses [105-107]. Some examples of LV vector-based vaccines are listed in the following Table 5. Although promising outcomes by lentiviral vector-based have been achieved in animal studies, the virulence of lentivirus still raises safety concerns. As the virulence of immunodeficiency virus is species-specific, feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV)-based vectors have been developed [108] to combat HIV-1 and the Herpes simplex virus (HSV) with great potential [109, 110].

| Disease | Vaccine component | Status | Clinical trials |

| Leukemia | LV-mediated genetically engineered AML cells | Phase I | NCT00718250 |

| ALL | LV-mediated IL-12 expression in AML cells | Phase I | NCT02483312 |

| CD19+ B cell Leukemia and Lymphoma | ARTEMIS™ | Early Phase 1 | NCT03895944 |

Advantages and disadvantages

Recombinant lentiviral vectors have a lot of advantages for vaccine development: ① mediating long-term and stable exogenous gene expression by integrating into the host genome; ② great packaging capacity; ③ highly efficient in transfection in both diving cells to non-dividing cells; ④ low pre-existing immunity. However, lentiviral-mediated gene integration into host genome, which might arouse the risk of tumorigenesis. Additionally, the virulence of lentiviral-derived backbone, i.e. HIV-1, also arouses serious safety concern.

Optimization

To avoid the virulence of HIV-1, FIV-based viral vectors [108] were discovered and showed great potential for the prevention of HIV-1 and HSV [109, 110]. Moreover, integration-deficient LV vectors are being exploited for vaccine development [111, 112].

4) Comparison of commonly used viral vector-based vaccines

Viral vector-based vaccines can provoke innate and adaptative immune responses in host system besides the transgene antigens, which makes them preferred during vaccine design and development. Nevertheless, the immune responses induced by different viral vectors may have some differences (Table 6). In brief, lentiviral vectors efficiently transduce antigen-presenting cells, but mediate exogenous gene integration into host genome, showing promising prospects as vaccine vectors, especially for the prevention of hematopoietic diseases. Adenoviral vectors induce high immune responses but have pre-existing immunity, exhibiting great promise in vaccine generation and gene therapy against cancers. Whereas, AAV vectors, just inducing mild immune responses and having a large number of serotypes, are the most excellent gene therapy vector but not very suitable to be vaccine vectors (Table 7).

| Viral vector | Lentiviral vector | Adenoviral vector | AAV vector |

| Virion and genome | Enveloped virus containing capsid and ~10-kb ssRNA genome | Capsid; 36-kb dsDNA genome | Capsid, 5-kb ssDNA genome (or ~2.5-kb scDNA genome) |

| Innate immunity | Strong IFNα/β response limits transduction and drives adaptive responses | Potent innate response, including activation of vascular endothelial cells and platelets, inflammatory cytokine production, and macrophage cell death | Comparatively weak and transient innate response; TLR9 signaling promotes CD8+ T cell responses; complement activation and other immunotoxicities seen in some patients receiving high-dose systemic gene transfer |

| Immunity in human population | Low pre-existing immunity | Pre-existing immunity to human serotypes | Pre-existing immunity varies between serotypes and geographic location |

In vivo transduction of antigen presenting cells | Efficient | Efficient | Inefficient |

| Use as vaccine carrier | Targeting of dendritic cells for vaccine development | Vaccine and cancer gene therapy applications | Limited |

| Adaptive immune responses to vector | NAB formation; possibly T cell responses to envelope protein | NAB formation; CD8+ T cell responses to viral gene products (except for high-capacity vectors) | NAB formation; CD8+ T cell responses to capsid |

| Adaptive immune responses to transgene products | Efficient inducer of B and T cell responses unless transgene expression is tightly controlled by miRNA and promoter and expression is professional APCs is eliminated | Efficient inducer of CD8+ T cell responses; antibody formation possible | Least efficient inducer of CD8+ T cells compared to Ad and LV; risk of CD8+ T cell and antibody responses highly variable depending on vector design and dose, route of administration, and host factors |

| Vector vaccines | Lentiviral vector-based vaccines | Adenoviral vector-based vaccines | AAV vector-based vaccines |

| Immune responses | Medium | Highest | Mild |

| Advantages | ① mediating long-term and stable exogenous gene expression by integrating into the host genome;

② great packaging capacity; ③ highly efficient in transfection in both diving cells to non-dividing cells; ④ low pre-existing immunity | ① well tolerated with no obvious influences on the cell viability after infection; ② great packaging capacity (up to 8kb); ③ broad range of infectivity; ④ high infection efficiency; ⑤ no integration ability into the host genome; ⑥ inducing a wide variety of immune responses. |

① superior biosafety rating; ② stable physical properties; ③ broad range of infectivity; ④ mediate long term and stable antigen gene expression. |

| Drawbacks | ① some risk of tumorigenesis; ② the virulence of vector backbone may raise some safety concern | ① inducing transient expression of antigen; ② pre-existing immunity and neutralizing antibodies (NAB); ③ recombinant Ad5-based vectors may have hepatotoxicity |

① limited cloning capacity ; ② only inducing mild immunity; ③ pre-existing immunity and neutralizing antibodies (NAB) |

| Packaging capacity | Medium | Highest | Lowest |

| Suitable for vaccine | Suitable | Most suitable | Not suitable |

GeneMedi provides professional services on viral packaging, you could find more information on the following website: https://www.genemedi.com/.

3. DNA based vaccines

Traditionally, vaccines are prepared with killed or attenuated viruses or bacteria, which might have serious security issues for the development of HIV vaccines. Additionally, vector-based vaccines may induce anti-vector immunity, which might interfere the immune responses provoked by vaccines [113]. Thus, DNA vaccines were first created in 1990 with finding that delivery of recombinant plasmid may allow the expression of exogenous antigen protein [114]. Then, the immune responses [115] and protection against lethal influenza by exogenous plasmid DNA were also discovered [116, 117]. Following these studies, DNA vaccines are demonstrated to be effective for the various diseases, such as infectious diseases, cancers, autoimmune diseases, and allergic diseases.

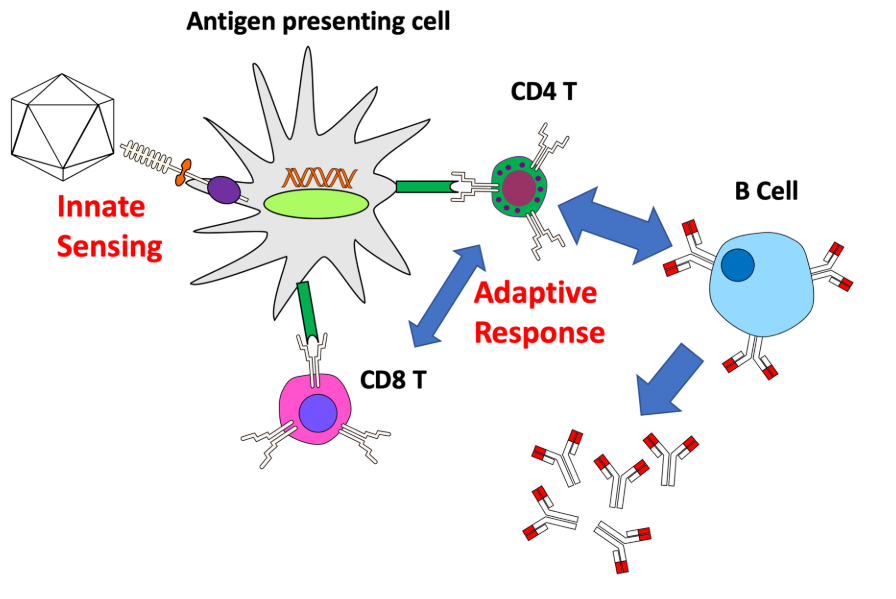

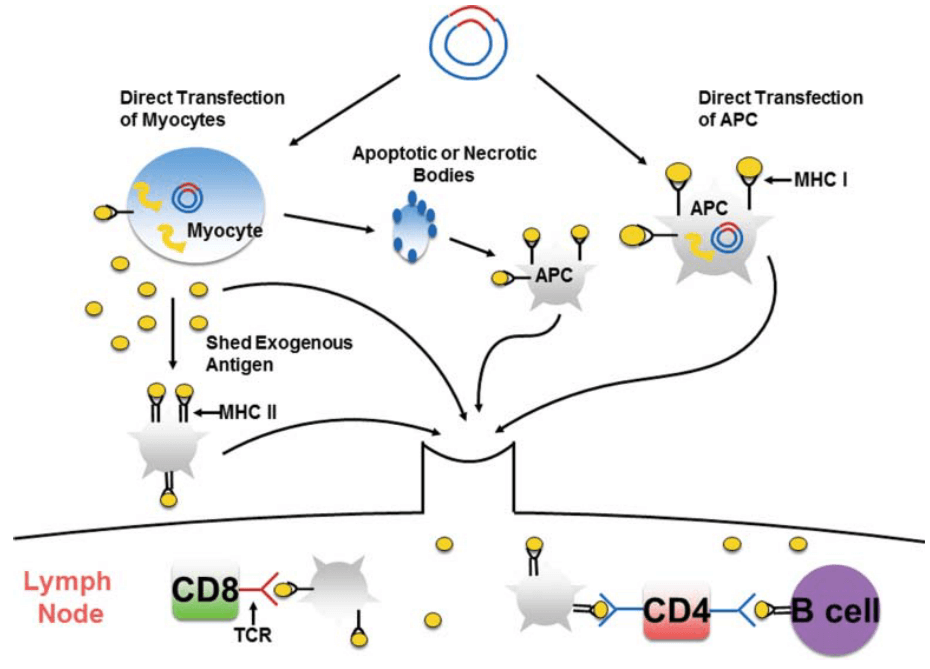

Generally, the optimized antigen DNA and molecular adjuvant are cloned into plasmid backbone, named as recombinant plasmid. After amplification and purification of the recombinant plasmids, they are delivered into host cells. Utilizing the nutrients and materials of host cells, antigens are transcribed, expressed, and assembled. On the one hand, antigen peptides are recognized and presented on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I, while secreted antigen proteins are captured and processed by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and then presented by MHC class II (MHC II). APCs carrying MHC-antigen peptide complex migrate to lymph node to stimulate T cells and mediate cellular immune response. On the other hand, antigen proteins can be recognized and captured by antigen-specific high affinity immunoglobulins on the B cell surface, then provoke humoral immune response, which is assisted by the pre-activated antigen-specific CD4+ T cells (Fig. 15) [118].

Compared with the traditional vaccines, the immunogenicity of DNA vaccines is quite weak. To enhance the immunogenicity, several strategies are utilized: ① stronger promoters are adopted for the cloning of recombinant plasmid, such as APC-specific promotors; ② optimize the delivery route, transducing DNA vaccines into antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells, may significantly promote the cytotoxic responses; ③ optimization of multiple antigen sequences; ④ adjuvants are used to prevent tolerance induction and facilitate the innate immune signals induced by DNA vaccines, including alum, liposome, nanoparticles, cytokines, chemokines and pathogen-recognition receptor (PRR) agonists; ⑤ circumvent potential inhibitory effects of the vector [119].

Although DNA vaccines have not been applied widespread due to their weak immunogenicity, promising outcomes are achieved based on improvements the priming high-level antigen specific antibody responses. Some of them are listed in the following Table 8 [120, 121].

| Disease | Antigen | Delivery route | Status | Outcome | Reference |

| HIV | EnV, ReV | Intramuscular | Phase I | Ab, CTL, T proliferative, chemokine release was observed | [122] |

| HIV | gp120, gp160 | Intramuscular | Phase I | No Ab response and cellular response were observed | [123] |

| HIV | ChAdV63 | Intramuscular | Phase II | No intervention-related serious adverse events | [124] |

| Malaria | 38 cytotoxic T cell epitopes and 16 helper T cell epitopes derived from P. falciparum antigens | Electroporation | Phase I | poorly immunogenic | [125] |

| Anal | HPV-16 E7 fragment | Intramuscular | Phase I | 10/12 patients developed antigen-specific immune responses | [126] |

| B-cell lymphoma | Idiotype | Intramuscular | Phase I/II | 1/12 patient developed T-cell response to autologous Id following initial immunization course; 6/12 patients developed anti-Id responses following booster immunization | [127] |

| Breast carcinoma | HER2 | Intramuscular | Phase I | 3/8 individuals had enhanced CD4+ T cell responses; 3/5 patients have enhanced HER2 Ab responses | [128] |

| Colorectal cancer | CEA fused to T-helper epitope | intradermal | Phase I | Erythema at injection site increased over time | [129] |

| Colorectal cancer | CEA (along with HBV surface antigen) | Intramuscular | Phase I | 4/17 patients developed Hsp65-specific IL-10 responses | [130] |

| Melanoma | gp 100 (mouse) | Intramuscular | Phase I | 4/27 patients developed gp100 tetramer+CD8+ cells; 5/27 developed IFNγ+CD8+ responses, one of which was tetramer+ | [131] |

| Melanoma | gp 101 (mouse and human) | Intramuscular | Phase I | 6/18 patients developed gp100-specific T cell responses | [132] |

| Melanoma | Tyrosinase (human and mouse) | Intramuscular | Phase I | 7/17 patients developed antigen-specific T-cell responses | [133] |

| Melanoma | MART-1 | Intramuscular | Phase I | No enhancement in antigen-specific immune responses | [134] |

| Melanoma | MART-1 and tyrosinase T-cell epitopes | Intra-lymph node | Phase I | 4/19 patients developed immune responses to MART-1 | [135] |

| Melanoma | Epitopes from five melanoma antigens | Intramuscular | Phase I | 22/31 patients developed antigen-specific T-cell responses | [136] |

| Melanoma | gp100 | PMED | Phase I | No antigen-specific immune responses detected | [137] |

| Melanoma | HLA-B7 | DNA-containing liposomes | Phase I | 2/22 patients developed enhanced TIL cytotoxicity | [138] |

| Melanoma | Tyrosinase epitopes | Intra-lymph node | Phase I | 11/26 patients had antigen-specific T-cell responses | [115] |

| NSCLC | L523S | Intramuscular | Phase I | 1/10 patient developed antigen-specific antibody response | [139] |

4. RNA based vaccines

Though DNA vaccines avoid the anti-vector immunity, long term existence in cells might produce excessive antigens, which might provoke overactive immune responses and exhaust T cells [140]. Thus, another kind of nucleic acid-based vaccines, RNA vaccines, were developed by directly delivering mRNA into cells for the prevention and therapy of diseases. Without the need to entry into cell nucleus, RNA vaccines mainly function in cytoplasm, which might have higher efficiency in delivery [141].

RNA vaccines can be classified into 2 categories: conventional mRNA-based vaccines and self-amplifying mRNA vaccines (SAM, also termed replicons) (Fig. 9) [142]. Upon entry into cells, conventional RNA vaccines directly generate antigens with nutrients and materials of host cells. On the contrary, SAM vaccines generate antigens by several steps (Fig. 16). SAM can self-replicate in host cells, thus they can mediate high expression levels of antigen. Due to no expression of structural proteins, no virion particle can be produced.

Besides the common immune responses induced by endogenous antigens, mRNA vaccine can elicit a robust type I IFN response, which facilitates CD8+ T cell cytolytic capacity and promotes eradication of infected cells [143]. However, some adverse effects are also observed. For example, specific single mutations in nsP1 sequence of alphaviruses, such as A533I, induce elevated Type I IFN expression, but decrease the expression level of antigen and vaccine immunity [144, 145]. To improve the efficacy of RNA vaccines, several strategies are applied: ① Modify or optimize the vaccine backbone, such as 5ʹ cap, poly (A) tail, codon optimization; ② Delivery systems (naked mRNA, formulation with liposomes, lipoplexes, polyplexes, particulate carrier-mediated, electroporation, and gene gun [146] ) and route of administration (such as intradermal [147] or intratumor administration [148]); ③ supplementation with small immunomodulatory molecules can also help improve the immune responses provoked by RNA vaccines, such as dexamethasone [149].

As a novel kind of vaccine, RNA vaccines have many advantages: ① Induction of humoral immune responses and cell immune responses; ② Provoke stronger immunity than DNA vaccines; ③ Avoid the anti-vector immunity; ④ Mediate transient expression of antigen; ⑤ No integration into host genome. To date, numerous mRNA vaccines have been translated into clinical trials, and several of them are listed in the following Table 9 [142].

| Disease | Antigen | Delivery route | Status | Outcome | Reference |

| Melanoma | NY-ESO-1, MAGE-A3, tyrosinase and TPTE | Intravenous | Phase I | IFNα and strong antigen-specific T-cell responses were induced | [150] |

| Non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) | NY-ESO-1, MAGEC1, MAGEC2, BIRC5, TPBG, and MUC1 | Intradermal | Phase I | Improved survival | [151] |

| Melanoma | Melan-A, Tyrosinase, gp100, Mage-A1, Mage-A3, and Survivin in 21 | Intradermal | Phase II | Vaccines are feasible and safe, and induce immune response | [152] |

| Melanoma | Melan-A, Tyrosinase, gp100, Mage-A1, Mage-A3, and Survivin in 22 | Intradermal | Phase I/II | An increase in antitumor humoral immune response was observed in some patient | [153] |

| Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) | Tumor-associated antigens mucin 1(MUC1), carcinoembryonic (CEA), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (Her-2/neu), telomerase, survivin, and melanoma-associated antigen 1 (MAGE-A1) | Intradermal | Phase I/II | Induce CD8+ and CD4+ immune Responses | [154] |

| Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) | MUC1, CEA, Her2/neu, telomerase, survivin, MAGE-A1 | Intradermal | Phase I/II | A clear correlation was observed between survival and immunological responses to TAAs | [155] |

| Rabies | Rabies virus glycoprotein (CV7201) | Intradermal or intramuscular | Phase I | Boostable functional antibodies against a viral antigen was observed when administered with a needle-free device | [156] |

| Flu | Hemagglutinin (HA) proteins | Intramuscular | Phase I | Protective immunogenicity with acceptable tolerability profiles were induced | [157] |

5. Vaccines development for COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a novel viral pneumonia caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). First discovered in Wuhan, a city in Hubei province of China, COVID-19 has already broken out throughout the world and posed a great threat to the public health, especially in Europe and North America now. Additionally, person-to-person transmission of COVID-19 disease is reported to be extremely rapid [158-160]. To date, more than one million cases were infected with COVID-19 and over 55,000 deaths occurred. Therefore, it is really urgent and noteworthy to develop the vaccines specific to COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2.

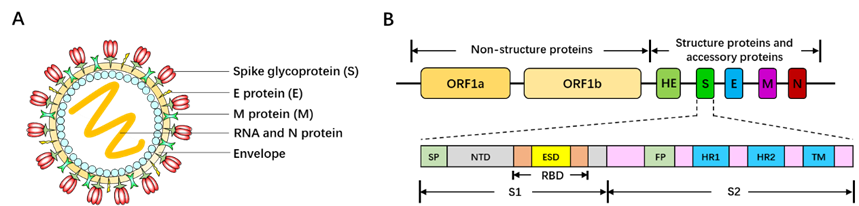

Belonging to the Betacoronavirus genus family, SARS-CoV-2 is 60~200nm in diameter and encapsidates a large positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus (26-32kb) with many spikes on the virus capsid (Fig. 17A). The RNA genome of SARS-CoV-2 encodes several accessory proteins and structural proteins, such as nucleocapsid (N) protein, envelope (E) protein, membrane (M) protein, and spike (S) protein (Fig. 10B). Although the detailed mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 infection has not been clearly illuminated, several studies demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 enters human cells via utilizing spike (S) protein to bind to the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE2) on the surface of target cell [161, 162].

Since the genome sequences of SARS-CoV were discovered and reported (https://www.gisaid.org/CoV2020/), a large number of pharmaceutical enterprises and research organizations are sparing all efforts to the vaccine development. Different companies utilize different targets and antigen epitopes. Some of the advances are listed in the following Table 10 (from WHO), and most of them focus on viral vector-based vaccines (replicating or non-replicating viral vector-based vaccines), recombinant protein (Spike), and nucleic acid-based vaccines. To date, two COVID-19 vaccines have entered Phase I clinical testing to assess the safety and potency of vaccines. One is mRNA-1273, was developed by Moderna Therapeutics, encoding a prefusion-stabilized form of Spike (S) protein [163] (https://www.nature.com/articles/d41587-020-00005-z). Another vaccine is recombinant protein of SARS-CoV-2 antigen, developed by Chinese Academy of Military Sciences, Institute of Military Medicine. It was predicted that these vaccines can be applied in clinics in a large scale as early as 2021 if they can successfully pass the clinical testing. Although there is a long way for theses vaccines to be applied for prevention and therapy of COVID-19, they indeed bring great hope and light to people all over the world.

| Platform | Type of candidate vaccine | Developer | Coronavirus target |

Current stage of clinical evaluation/regulatory status- Coronavirus candidate |

Same platform for non-Coronavirus candidates |

| DNA | DNA plasmid vaccine Electroporation device | Inovio Pharmaceuticals | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | Lassa, Nipah; HIV; Filovirus; HPV; Cancer indications; Zika; Hepatitis B |

| DNA | DNA | Takis/Applied DNA Sciences/Evvivax | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | |

| DNA | DNA plasmid vaccine | Zydus Cadila | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | |

| Live Attenuated Virus | Deoptimized live attenuated vaccines | Codagenix/Serum Institute of India | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | HAV, InfA, ZIKV, FMD, SIV, RSV, DENV |

| Non-Replicating Viral Vector | MVA encoded VLP | GeoVax/BravoVax | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | LASV, EBOV, MARV, HIV |

| Non-Replicating Viral Vector | Ad26 (alone or with MVA boost) | Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | Ebola, HIV, RSV |

| Non-Replicating Viral Vector | ChAdOx1 | University of Oxford | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | Influenza, TB, Chikungunya, Zika, MenB, plague |

| Non-Replicating Viral Vector | Adenovirus-based NasoVAX | Altimmune | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | Influenza |

| Non-Replicating Viral Vector | Ad5 S (GREVAX™ platform) | Greffex | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | MERS |

| Non-Replicating Viral Vector | Oral Vaccine platform | Vaxart | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | InfA, CHIKV, LASV, NORV; EBOV, RVF, HBV, VEE |

| Non-Replicating Viral Vector | Viral-vectored based | CanSino Biologics | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | |

| Protein Subunit | Drosophila S2 insect cell expression system VLPs | ExpreS2ion | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | |

| Protein Subunit | S protein | WRAIR/USAMRIID | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | |

| Protein Subunit | S-Trimer | Clover Biopharmaceuticals Inc./GSK | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | HIV, REV Influenza |

| Protein Subunit | Peptide | Vaxil Bio | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | |

| Protein Subunit | Ii-Key peptide | Generex/EpiVax | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | Influenza, HIV, SARS-CoV |

| Protein Subunit | S protein | EpiVax/Univ. of Georgia | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | H7N9 |

| Protein Subunit | S protein (baculovirus production) | Sanofi Pasteur | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | Influenza, SARS-CoV |

| Protein Subunit | Full length S trimers/ nanoparticle + Matrix M | Novavax | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | RSV; CCHF, HPV, VZV, EBOV |

| Protein Subunit | S protein clamp | University of Queensland/GSK | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | Nipah, influenza, Ebola, Lassa |

| Protein Subunit | S1 or RBD protein | Baylor, New York Blood Center, Fudan University | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | SARS, MERS |

| Protein Subunit | Subunit protein, plant produced | iBio/CC-Pharming | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | |

| Replicating Viral Vector | Measles Vector | Zydus Cadila | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | |

| Replicating Viral Vector | Measles Vector | Institute Pasteur | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | West nile, chik, Eobla, Lassa, Zika |

| Replicating Viral Vector | Horsepox vector | Tonix Pharma/Southern Research | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | Smallpox, monkeypox |

| RNA | mRNA | China CDC/Tongji University/Stermina | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | |

| RNA | mRNA | Moderna/NIAID | COVID-19 | Phase I clinical trial | Multiple candidates |

| RNA | mRNA | Arcturus/Duke-NUS | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | Multiple candidates |

| RNA | saRNA | Imperial College London | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | EBOV; LASV, MARV, Inf (H7N9), RABV |

| RNA | mRNA | Curevac | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | RABV, LASV, YFV; MERS, InfA, ZIKV, DengV, NIPV |

| Unknown | Unknown | University of Pittsburgh | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | |

| Unknown | Unknown | University of Saskatchewan | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | |

| Unknown | Unknown | ImmunoPrecise | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | |

| Unknown | Unknown | MIGAL Galilee Research Institute | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical | |

| Unknown | Unknown | Doherty Institute | COVID-19 | Pre-Clinical |

6. Tumor/Cancer vaccines

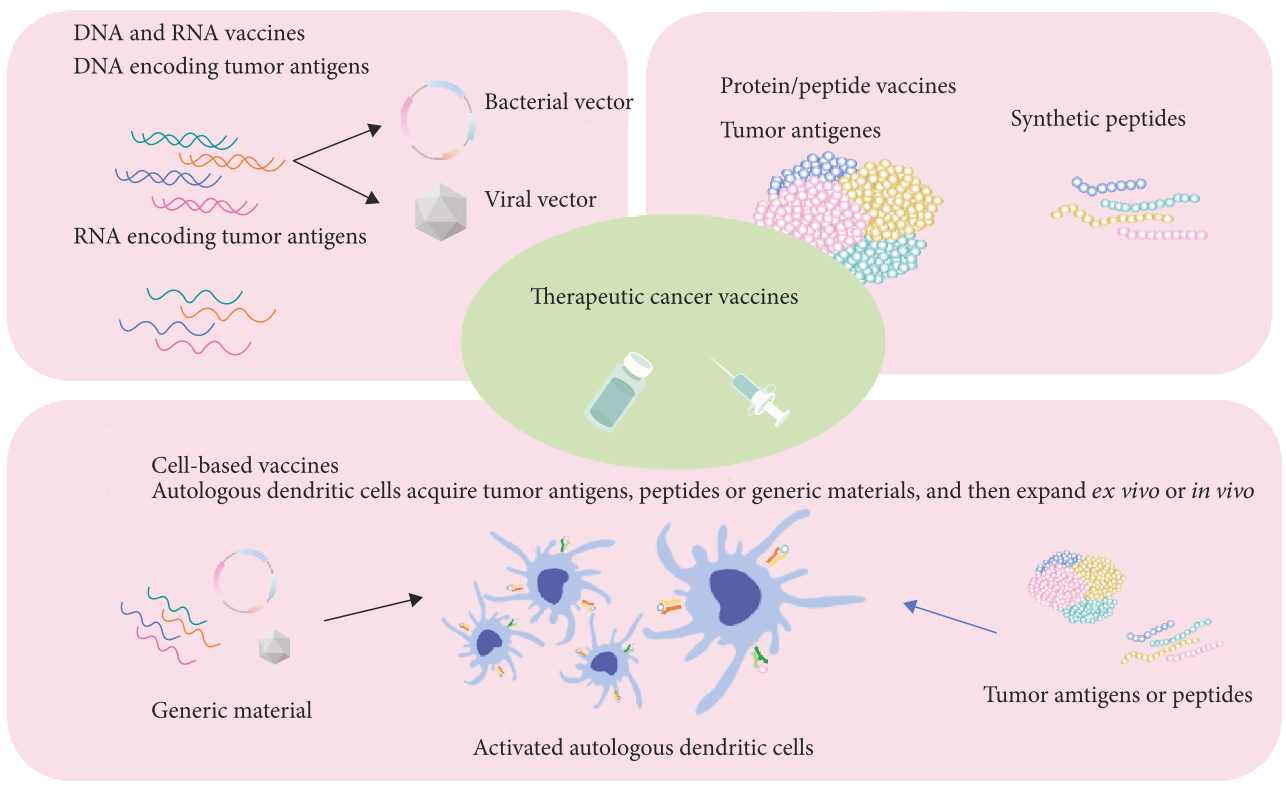

Despite several decades’ continuous efforts on tumor therapy with radiation treatment and chemotherapy, serious adverse effects, including nausea, vomiting, physical weakness, mental malaise, sweating, decreased white blood cells and platelets, are really painful and intolerable. Tumor vaccines are vaccines using tumor-specific antigens (TSAs) to provoke the host immune system to specifically eliminate and suppress tumors or cancers, exhibiting promising advantages over traditional radiation and chemotherapy. Several kinds of tumor vaccines are developed for the therapy of tumor as shown in Fig. 18 [164], including nucleic acid vaccines (DNA vaccines and RNA vaccines), protein/peptide vaccines, and cell-based vaccines with tumor antigens.

Nucleic acid-based vaccines can be taken up by APCs and translated into specific antigen to provoke host immune system, such as Tyrosinase Related Protein 1 (TYRP1/gp75) vaccine for the treatment of melanoma [165]. Protein/peptide-based vaccines are tumor specific antigens protein or epitope, which can directly stimulate immune system, such as HSPPC-96 vaccine (Oncophage) for the treatment of melanoma, gastric cancer, renal cell cancer, lymphoma, and pancreatic cancer [166]. Cell-based vaccines are autologous dendritic cells or other immune cells with insertion of tumor antigen genes or transfected with tumor antigens or peptides, such as dendritic cell vaccine, provenge (sipuleucel-T), targeting PAP for the therapy of prostate cancer [167]. A large number of tumor vaccines have been translated into clinics and encouraging therapy outcomes have been achieved (Table 11).

| Disease | Antigen/target | Vaccine classification |

Delivery route | Status | Outcome | References |

| Prostate cancer | PAP | DNA vaccine | Intravenous | Phase III | Improved survival | [167] |

| Prostate cancer | VEGF Receptor 2 | DNA vaccine | Oral | Phase I | Vaccine were well-tolerated and T effector was increased | [168] |

| NSCLC | MUC1 | Protein/peptide-based vaccines | Intravenous | Phase III | Tecemotide might have some adverse events on patients who initially receive concurrent chemoradiotherapy | [169] |

| NSCLC | MUC1 | Protein/peptide-based vaccines | Subcutaneous | Phase III | Safe, but adverse events existed | [170] |

| Melanoma | HSPPC-96 | Protein/peptide-based vaccines | Intradermal | Phase I/II | Feasible and safe. Modest immune response and anti-tumor activity were observed | [171] |

| Ovarian carcinoma, glioblastoma, pancreatic carcinoma, stomach carcinoma | Multiple tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) | Tumor cell vaccine | Intradermal | Phase I/II | Antitumor immune memory and patient survival were improved | [172] |

| Prostate cancer | PAP | Recombinant adenoviral vector-based vaccine | Subcutaneous | Phase I/II | Safe with no serious vaccine-related adverse events, and anti-PSA T-cell responses were induced | [172] |

| Melanoma | IL-2 | Autologous tumor cell vaccine via Ad vector-mediated IL-2 transfection | Intradermal/subcutaneous | Phase I | Safe and tolerate | [173] |

| Melanoma | MART-1 or gp100 | Recombinant adenoviral vector-based vaccine | Intramuscular/subcutaneous | Phase I | Safe, but presenting high levels of neutralizing antibody. | [174] |

| Melanoma | GM-CSF | Irradiated autologous tumor cell vaccine via Ad vector-mediated GM-CSF transfection | Intradermal/subcutaneous | Phase I | Well tolerated and induce anti-tumor immune response | [175] |

| Melanoma | MART-1 | Autologous dendritic cell vaccine via Ad vector-mediated MART-1 transfection | Intradermal | Phase I/II | Safe and immunogenic | [176] |

| Solid tumor | HER2 | DNA vaccine and adenoviral vector-based vaccine | Intramuscular | Phase I | Well tolerated and without any serious adverse events | [79] |

| Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) | IFNα/Syn3 | Recombinant adenoviral vector-based vaccine | Intravesical | Phase II | Well tolerated | [177] |

| Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) | IFNα2b/Syn4 | Recombinant adenoviral vector-based vaccine | Intravesical | Phase Ib | Promising drug efficacy was shown | [178] |

| Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) | IFNα/Syn3 | Recombinant adenoviral vector-based vaccine | Intravesical | Phase I | Well tolerated with no dose limiting toxicity | [179] |

| Colorectal cancer | CEA | Recombinant adenoviral vector-based vaccine | Subcutaneous | Phase I/II | Safe and immunogenic | [179] |

| Colorectal cancer | CEA | Recombinant adenoviral vector-based vaccine | Subcutaneous | Phase I | Minimal toxicity | [180] |

| Hepatocellular cancer | AFP | DNA vaccine and adenoviral vector-based vaccine | Intramuscular | Phase I | Safe and immunogenic | [181] |

| B-cell lymphosarcoma | Telomerase | Recombinant adenoviral vector-based vaccine | In femoral biceps | Phase I | Safe and prolong the survival time | [182] |

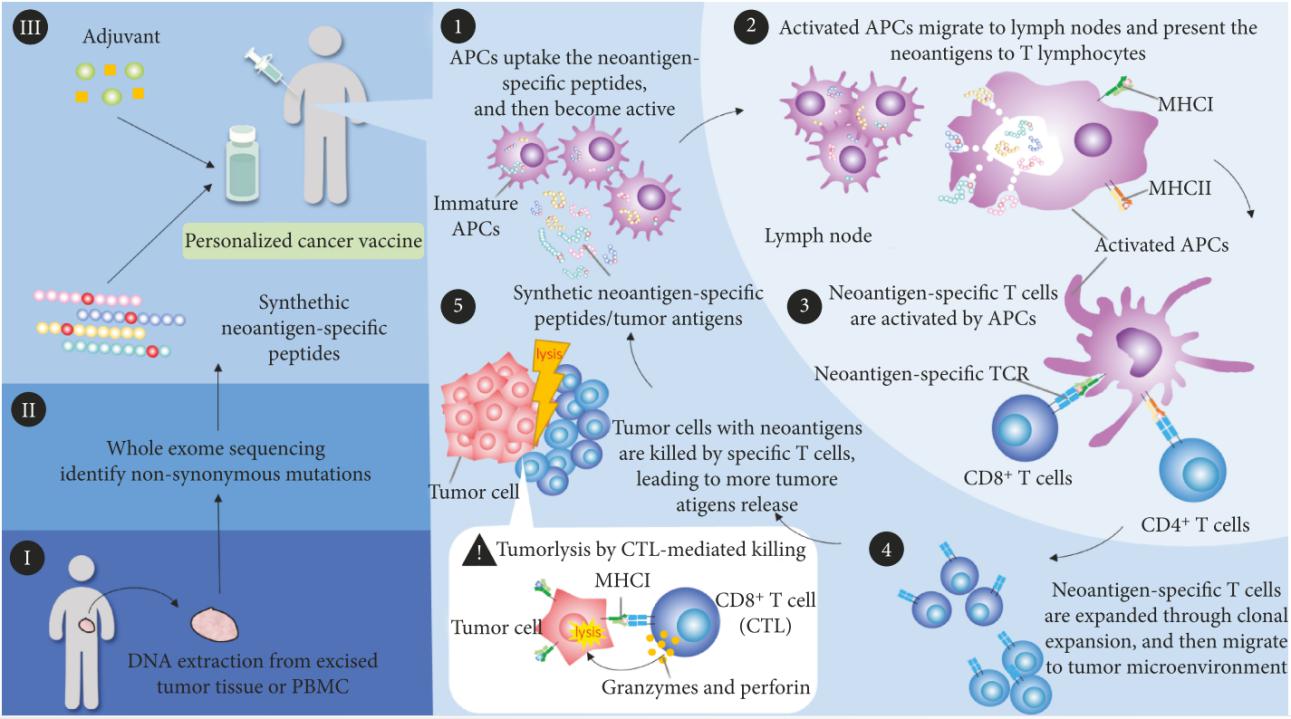

As is known to all, there are many somatic mutations in tumors varying in different individuals, and more and more highly heterogeneous neoantigens are discovered and identified through next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies. On the basis of tumor mutation profiles, personalized cancer vaccines are designed and developed to activate immune system against cancer by targeting specific epitopes of neoantigens (Fig. 19). Once delivered into the body with adjuvant, personal vaccines provokes host immune responses through the following processes:

① Neoantigen-specific peptides inside personal vaccines are captured and processed by APCs;

② Activated APCs migrate to lymph nodes and present neoantigens to T cells with MHC molecules;

③ Neoantigens are recognized and bound by T cell receptor, thus priming and activating cell immunity;

④ Neoantigen-specific T cells are expanded, migrate and infiltrate to tumor microenvironment;

⑤ Neoantigen-specific T cells kill tumor cells with neoantigens, leading to the release of more antigens, which elicits adaptive immune memory and augments the immune responses.

So far, personal vaccines have achieved encouraging anti-tumor effects in the pre-clinical studies with mouse models and clinical trials. For example, using whole-exome and transcriptome sequencing and mass spectrometry analysis, more than 1300 amino acid changes were identified in MC-38 and TRAMP-C1 murine tumor models, and vaccination with mutated peptides exhibits remarkable and sustainable inhibition of tumor growth [183]. For human melanoma therapy, a neoantigen was discovered via whole exome sequencing and HLA binding prediction algorithm, and dendritic cell vaccine with the neoantigen significantly enhances the T cell immune response to the neoantigen in some patients [184].

7. Summary

In summary, different kinds of vaccines have their specific advantages and disadvantages (Table 12), and people should select the most suitable vaccines according to their demands. Although nucleic acid-based vaccines need short-term and little cost, DNA-based vaccines provoke mild immune responses, and no available mRNA vaccines have been applied into clinics, which really restrict the application of nucleic acid-based vaccines. Viral vector-based vaccines, especially adenoviral vector-based vaccines, stimulate relatively stronger immune responses, showing unique superiority in vaccine development. However, the COVID-19 is raging across the world now, which makes the vaccines for COVID-19 urgently demanded. At this fierce moment, time is really precious for life, which might give a chance for mRNA vaccine. At the same time, as a kind of effective and efficacious vaccines, viral vector-based vaccines are also promising and with great prospect for COVID-19 vaccine development.

Vaccine classification |

Viral vector-based vaccines | DNA vaccine | RNA vaccine |

| Immune responses | Induce humoral and cellular immunity | Induce humoral and cellular immunity | Induce humoral and cellular immunity |

| Immunogenicity | Varies with different vectors | Weak | Weak |

| Advantages | ①highly efficient in gene transduction; ② mediate specific gene delivery to target cells; ③induce of both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses; ④ better efficacy and safety; ⑤ just need low administration dose; ⑥ easy to be applied into large-scale manufacturing; ⑦ possessing widespread potential target diseases, ranging from infectious diseases to cancers |

① Induction of humoral immune responses and cell immune responses; ② Avoid the anti-vector immunity; ③ Easy to produce in a large scale |

① Induction of humoral immune responses and cell immune responses; ② Provoke stronger immunity than DNA vaccines; ③ Avoid the anti-vector immunity; ④ Mediate transient expression of antigen; ⑤ No integration into host genome; ⑥ Easy to produce in a large scale |

| Drawbacks | Pre-existing immunity and neutralizing antibodies (AAV and AdV); tumorigenicity (LV) | Induce weak immunity | Induce weak immunity |

| Suitable time | AAV and LV: long-term stable expression; AdV: transient | Transient | Transient |

| Delivery system | Viral vector | Naked nucleic acids, formulation with liposomes, lipoplexes, polyplexes, particulate carrier-mediated, electroporation, and gene gun | Naked nucleic acids, formulation with liposomes, lipoplexes, polyplexes, particulate carrier-mediated, electroporation, and gene gun |

| Optimization | AAV: rational design of capsid; AdV: modify fiber protein to alter tissue tropism; LV: develop integration-free vector |

① Utilizing stronger promoters; ② Optimize the delivery route; ③ Optimization of multiple antigen sequences; ④ Adjuvants are used to prevent tolerance induction and facilitate the innate immune signals; ⑤ circumvent potential inhibitory effects of the vector |

① Modify or optimize the vaccine backbone; ② Optimize the delivery systems and route of administration; ③ supplementation with small immunomodulatory molecules to improve the immune responses |

| Clinical usage | Yes | Not yet | Not yet |

8. References

1.Ura T, Okuda K, Shimada M. Developments in Viral Vector-Based Vaccines. Vaccines (Basel). 2014;2:624-641.

2.Shirley JL, de Jong YP, Terhorst C, Herzog RW. Immune Responses to Viral Gene Therapy Vectors. Mol Ther. 2020;28:709-722.

3.Atchison RW, Casto BC, Hammon WM. Adenovirus-Associated Defective Virus Particles. Science. 1965;149:754-756.

4.Hoggan MD, Blacklow NR, Rowe WP. Studies of small DNA viruses found in various adenovirus preparations: physical, biological, and immunological characteristics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of

5.Bartlett JS, Wilcher R, Samulski RJ. Infectious entry pathway of adeno-associated virus and adeno-associated virus vectors. Journal of virology. 2000;74:2777-2785.

6.Ding W, Zhang L, Yan Z, Engelhardt JF. Intracellular trafficking of adeno-associated viral vectors. Gene therapy. 2005;12:873-880.

7.Srivastava A. Adeno-associated virus-mediated gene transfer. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2008;105:17-24.

8.Berns KI. Parvovirus replication. Microbiological reviews. 1990;54:316-329.

9.Pereira DJ, McCarty DM, Muzyczka N. The adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep protein acts as both a repressor and an activator to regulate AAV transcription during a productive infection. Journal of virology. 1997;71:1079-1088.

10.Zhu J, Huang X, Yang Y. The TLR9-MyD88 pathway is critical for adaptive immune responses to adeno-associated virus gene therapy vectors in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2388-2398.

11.Hosel M, Broxtermann M, Janicki H, Esser K, Arzberger S, Hartmann P, et al. Toll-like receptor 2-mediated innate immune response in human nonparenchymal liver cells toward adeno-associated viral vectors. Hepatology. 2012;55:287-297.

12.Pien GC, Basner-Tschakarjan E, Hui DJ, Mentlik AN, Finn JD, Hasbrouck NC, et al. Capsid antigen presentation flags human hepatocytes for destruction after transduction by adeno-associated viral vectors. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1688-1

13.Shirley JL, Keeler GD, Sherman A, Zolotukhin I, Markusic DM, Hoffman BE, et al. Type I IFN Sensing by cDCs and CD4(+) T Cell Help Are Both Requisite for Cross-Priming of AAV Capsid-Specific CD8(+) T Cells. Mol Ther. 2020;28:758-770.

14.Sudres M, Cire S, Vasseur V, Brault L, Da Rocha S, Boisgerault F, et al. MyD88 signaling in B cells regulates the production of Th1-dependent antibodies to AAV. Mol Ther. 2012;20:1571-1581.

15.Rabinowitz J, Chan YK, Samulski RJ. Adeno-associated Virus (AAV) versus Immune Response. Viruses. 2019;11.

16.Weitzman MD, Linden RM. Adeno-associated virus biology. Methods in molecular biology. 2011;807:1-23.

17.Vectors used in gene therapy clinical trials. The Journal of Gene Medicine Online Library. [Online] Updated Nov 2017.

18.Kassner U, Hollstein T, Grenkowitz T, Wuhle-Demuth M, Salewsky B, Demuth I, et al. Gene Therapy in Lipoprotein Lipase Deficiency: Case Report on the First Patient Treated with Alipogene Tiparvovec Under Daily Practice Conditions. Hum

19.Passini MA, Bu J, Richards AM, Treleaven CM, Sullivan JA, O’Riordan CR, et al. Translational fidelity of intrathecal delivery of self-complementary AAV9-survival motor neuron 1 for spinal muscular atrophy. Human gene therapy. 2014;25

20.Stieger K, Lorenz B. [Specific gene therapy for hereditary retinal dystrophies – an update]. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 2014;231:210-215.

21.Trapani I, Colella P, Sommella A, Iodice C, Cesi G, de Simone S, et al. Effective delivery of large genes to the retina by dual AAV vectors. EMBO molecular medicine. 2014;6:194-211.

22.Doi K, Takeuchi Y. Gene therapy using retrovirus vectors: vector development and biosafety at clinical trials. Uirusu. 2015;65:27-36.

23.Duncan GA, Kim N, Colon-Cortes Y, Rodriguez J, Mazur M, Birket SE, et al. An Adeno-Associated Viral Vector Capable of Penetrating the Mucus Barrier to Inhaled Gene Therapy. Molecular therapy. Methods & clinical development. 2018;9:29

24.Bowles DE, McPhee SW, Li C, Gray SJ, Samulski JJ, Camp AS, et al. Phase 1 gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy using a translational optimized AAV vector. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therap

25.Nathwani AC, Tuddenham EG, Rangarajan S, Rosales C, McIntosh J, Linch DC, et al. Adenovirus-associated virus vector-mediated gene transfer in hemophilia B. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365:2357-2365.

26.Jessup M, Greenberg B, Mancini D, Cappola T, Pauly DF, Jaski B, et al. Calcium Upregulation by Percutaneous Administration of Gene Therapy in Cardiac Disease (CUPID): a phase 2 trial of intracoronary gene therapy of sarcoplasmic reti

27.LeWitt PA, Rezai AR, Leehey MA, Ojemann SG, Flaherty AW, Eskandar EN, et al. AAV2-GAD gene therapy for advanced Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, sham-surgery controlled, randomised trial. The Lancet. Neurology. 2011;10:309-319.

28.Aalbers CJ, Bevaart L, Loiler S, de Cortie K, Wright JF, Mingozzi F, et al. Preclinical Potency and Biodistribution Studies of an AAV 5 Vector Expressing Human Interferon-beta (ART-I02) for Local Treatment of Patients with Rheumatoid

29.Bevaart L, Aalbers CJ, Vierboom MP, Broekstra N, Kondova I, Breedveld E, et al. Safety, Biodistribution, and Efficacy of an AAV-5 Vector Encoding Human Interferon-Beta (ART-I02) Delivered via Intra-Articular Injection in Rhesus Monke

30.Xin KQ, Urabe M, Yang J, Nomiyama K, Mizukami H, Hamajima K, et al. A novel recombinant adeno-associated virus vaccine induces a long-term humoral immune response to human immunodeficiency virus. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:1047-1061.

31.Xin KQ, Ooki T, Mizukami H, Hamajima K, Okudela K, Hashimoto K, et al. Oral administration of recombinant adeno-associated virus elicits human immunodeficiency virus-specific immune responses. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:1571-1581.

32.Xin KQ, Mizukami H, Urabe M, Toda Y, Shinoda K, Yoshida A, et al. Induction of robust immune responses against human immunodeficiency virus is supported by the inherent tropism of adeno-associated virus type 5 for dendritic cells. J

33.Lin J, Calcedo R, Vandenberghe LH, Bell P, Somanathan S, Wilson JM. A new genetic vaccine platform based on an adeno-associated virus isolated from a rhesus macaque. J Virol. 2009;83:12738-12750.

34.Nieto K, Stahl-Hennig C, Leuchs B, Muller M, Gissmann L, Kleinschmidt JA. Intranasal vaccination with AAV5 and 9 vectors against human papillomavirus type 16 in rhesus macaques. Hum Gene Ther. 2012;23:733-741.

35.Grieger JC, Samulski RJ. Packaging capacity of adeno-associated virus serotypes: impact of larger genomes on infectivity and postentry steps. Journal of virology. 2005;79:9933-9944.

36.Fitzpatrick Z, Leborgne C, Barbon E, Masat E, Ronzitti G, van Wittenberghe L, et al. Influence of Pre-existing Anti-capsid Neutralizing and Binding Antibodies on AAV Vector Transduction. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2018;9:119-129.

37.Kotterman MA, Schaffer DV. Engineering adeno-associated viruses for clinical gene therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:445-451.

38.Grimm D, Zolotukhin S. E Pluribus Unum: 50 Years of Research, Millions of Viruses, and One Goal–Tailored Acceleration of AAV Evolution. Mol Ther. 2015;23:1819-1831.

39.Maheshri N, Koerber JT, Kaspar BK, Schaffer DV. Directed evolution of adeno-associated virus yields enhanced gene delivery vectors. Nature biotechnology. 2006;24:198-204.

40.Khabou H, Desrosiers M, Winckler C, Fouquet S, Auregan G, Bemelmans AP, et al. Insight into the mechanisms of enhanced retinal transduction by the engineered AAV2 capsid variant -7m8. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 2016;113:2712-2

41.Kienle E, Senis E, Borner K, Niopek D, Wiedtke E, Grosse S, et al. Engineering and evolution of synthetic adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene therapy vectors via DNA family shuffling. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2012.

42.Rowe WP, Huebner RJ, Gilmore LK, Parrott RH, Ward TG. Isolation of a cytopathogenic agent from human adenoids undergoing spontaneous degeneration in tissue culture. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. So

43.Wong CM, McFall ER, Burns JK, Parks RJ. The role of chromatin in adenoviral vector function. Viruses. 2013;5:1500-1515.

44.Ranki T, Hemminki A. Serotype chimeric human adenoviruses for cancer gene therapy. Viruses. 2010;2:2196-2212.

45.Ison MG, Hayden RT. Adenovirus. Microbiology spectrum. 2016;4.

46.Vorburger SA, Hunt KK. Adenoviral gene therapy. The oncologist. 2002;7:46-59.

47.Seiler MP, Cerullo V, Lee B. Immune response to helper dependent adenoviral mediated liver gene therapy: challenges and prospects. Curr Gene Ther. 2007;7:297-305.

48.Othman M, Labelle A, Mazzetti I, Elbatarny HS, Lillicrap D. Adenovirus-induced thrombocytopenia: the role of von Willebrand factor and P-selectin in mediating accelerated platelet clearance. Blood. 2007;109:2832-2839.

49.Atasheva S, Shayakhmetov DM. Adenovirus sensing by the immune system. Curr Opin Virol. 2016;21:109-113.

50.Doronin K, Flatt JW, Di Paolo NC, Khare R, Kalyuzhniy O, Acchione M, et al. Coagulation factor X activates innate immunity to human species C adenovirus. Science. 2012;338:795-798.

51.Tam JC, Bidgood SR, McEwan WA, James LC. Intracellular sensing of complement C3 activates cell autonomous immunity. Science. 2014;345:1256070.

52.Parker AL, Waddington SN, Nicol CG, Shayakhmetov DM, Buckley SM, Denby L, et al. Multiple vitamin K-dependent coagulation zymogens promote adenovirus-mediated gene delivery to hepatocytes. Blood. 2006;108:2554-2561.

53.Shayakhmetov DM, Gaggar A, Ni S, Li ZY, Lieber A. Adenovirus binding to blood factors results in liver cell infection and hepatotoxicity. J Virol. 2005;79:7478-7491.

54.Allen RJ, Byrnes AP. Interaction of adenovirus with antibodies, complement, and coagulation factors. FEBS Lett. 2019;593:3449-3460.

55.Cotter MJ, Zaiss AK, Muruve DA. Neutrophils interact with adenovirus vectors via Fc receptors and complement receptor 1. J Virol. 2005;79:14622-14631.

56.McEwan WA, Tam JC, Watkinson RE, Bidgood SR, Mallery DL, James LC. Intracellular antibody-bound pathogens stimulate immune signaling via the Fc receptor TRIM21. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:327-336.

57.Fletcher AJ, James LC. Coordinated Neutralization and Immune Activation by the Cytosolic Antibody Receptor TRIM21. J Virol. 2016;90:4856-4859.

58.Khare R, Hillestad ML, Xu Z, Byrnes AP, Barry MA. Circulating antibodies and macrophages as modulators of adenovirus pharmacology. J Virol. 2013;87:3678-3686.

59.Bottermann M, Foss S, van Tienen LM, Vaysburd M, Cruickshank J, O’Connell K, et al. TRIM21 mediates antibody inhibition of adenovirus-based gene delivery and vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:10440-10445.

60.Di Paolo NC, Baldwin LK, Irons EE, Papayannopoulou T, Tomlinson S, Shayakhmetov DM. IL-1alpha and complement cooperate in triggering local neutrophilic inflammation in response to adenovirus and eliminating virus-containing cells. PL

61.Di Paolo NC, Miao EA, Iwakura Y, Murali-Krishna K, Aderem A, Flavell RA, et al. Virus binding to a plasma membrane receptor triggers interleukin-1 alpha-mediated proinflammatory macrophage response in vivo. Immunity. 2009;31:110-121.

62.Muruve DA, Petrilli V, Zaiss AK, White LR, Clark SA, Ross PJ, et al. The inflammasome recognizes cytosolic microbial and host DNA and triggers an innate immune response. Nature. 2008;452:103-107.

63.Suzuki M, Bertin TK, Rogers GL, Cela RG, Zolotukhin I, Palmer DJ, et al. Differential type I interferon-dependent transgene silencing of helper-dependent adenoviral vs. adeno-associated viral vectors in vivo. Mol Ther. 2013;21:796-80

64.Anghelina D, Lam E, Falck-Pedersen E. Diminished Innate Antiviral Response to Adenovirus Vectors in cGAS/STING-Deficient Mice Minimally Impacts Adaptive Immunity. J Virol. 2016;90:5915-5927.

65.Wang L, Wen M, Cao X. Nuclear hnRNPA2B1 initiates and amplifies the innate immune response to DNA viruses. Science. 2019;365.

66.Avgousti DC, Herrmann C, Kulej K, Pancholi NJ, Sekulic N, Petrescu J, et al. A core viral protein binds host nucleosomes to sequester immune danger signals. Nature. 2016;535:173-177.

67.Fields PA, Kowalczyk DW, Arruda VR, Armstrong E, McCleland ML, Hagstrom JN, et al. Role of vector in activation of T cell subsets in immune responses against the secreted transgene product factor IX. Mol Ther. 2000;1:225-235.

68.Amalfitano A, Parks RJ. Separating fact from fiction: assessing the potential of modified adenovirus vectors for use in human gene therapy. Current gene therapy. 2002;2:111-133.

69.Appaiahgari MB, Vrati S. Adenoviruses as gene/vaccine delivery vectors: promises and pitfalls. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2015;15:337-351.

70.Sweeney K, Hallden G. Oncolytic adenovirus-mediated therapy for prostate cancer. Oncolytic virotherapy. 2016;5:45-57.

71.Castro JE, Melo-Cardenas J, Urquiza M, Barajas-Gamboa JS, Pakbaz RS, Kipps TJ. Gene immunotherapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a phase I study of intranodally injected adenovirus expressing a chimeric CD154 molecule. Cancer resea

72.Predina JD, Keating J, Venegas O, Nims S, Singhal S. Neoadjuvant intratumoral immuno-gene therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Discovery medicine. 2016;21:275-281.

73.Schiza A, Wenthe J, Mangsbo S, Eriksson E, Nilsson A, Totterman TH, et al. Adenovirus-mediated CD40L gene transfer increases Teffector/Tregulatory cell ratio and upregulates death receptors in metastatic melanoma patients. Journal of

74.Garcia-Carbonero R, Salazar R, Duran I, Osman-Garcia I, Paz-Ares L, Bozada JM, et al. Phase 1 study of intravenous administration of the chimeric adenovirus enadenotucirev in patients undergoing primary tumor resection. Journal for i

75.Hammer SM, Sobieszczyk ME, Janes H, Karuna ST, Mulligan MJ, Grove D, et al. Efficacy trial of a DNA/rAd5 HIV-1 preventive vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2083-2092.

76.Kibuuka H, Kimutai R, Maboko L, Sawe F, Schunk MS, Kroidl A, et al. A phase 1/2 study of a multiclade HIV-1 DNA plasmid prime and recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 boost vaccine in HIV-Uninfected East Africans (RV 172). J Infect Dis.

77.Gurwith M, Lock M, Taylor EM, Ishioka G, Alexander J, Mayall T, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an oral, replicating adenovirus serotype 4 vector vaccine for H5N1 influenza: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1

78.Smaill F, Jeyanathan M, Smieja M, Medina MF, Thanthrige-Don N, Zganiacz A, et al. A human type 5 adenovirus-based tuberculosis vaccine induces robust T cell responses in humans despite preexisting anti-adenovirus immunity. Sci Transl

79.Diaz CM, Chiappori A, Aurisicchio L, Bagchi A, Clark J, Dubey S, et al. Phase 1 studies of the safety and immunogenicity of electroporated HER2/CEA DNA vaccine followed by adenoviral boost immunization in patients with solid tumors.

80.Kallel H, Kamen AA. Large-scale adenovirus and poxvirus-vectored vaccine manufacturing to enable clinical trials. Biotechnol J. 2015;10:741-747.

81.Perreau M, Pantaleo G, Kremer EJ. Activation of a dendritic cell-T cell axis by Ad5 immune complexes creates an improved environment for replication of HIV in T cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2717-2725.

82.Sekaly RP. The failed HIV Merck vaccine study: a step back or a launching point for future vaccine development? J Exp Med. 2008;205:7-12.

83.Fausther-Bovendo H, Kobinger GP. Pre-existing immunity against Ad vectors: humoral, cellular, and innate response, what’s important? Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10:2875-2884.

84.Yang Y, Nunes FA, Berencsi K, Furth EE, Gonczol E, Wilson JM. Cellular immunity to viral antigens limits E1-deleted adenoviruses for gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4407-4411.

85.Xin KQ, Jounai N, Someya K, Honma K, Mizuguchi H, Naganawa S, et al. Prime-boost vaccination with plasmid DNA and a chimeric adenovirus type 5 vector with type 35 fiber induces protective immunity against HIV. Gene Ther. 2005;12:1769

86.Gao GP, Yang Y, Wilson JM. Biology of adenovirus vectors with E1 and E4 deletions for liver-directed gene therapy. J Virol. 1996;70:8934-8943.

87.Okada N, Iiyama S, Okada Y, Mizuguchi H, Hayakawa T, Nakagawa S, et al. Immunological properties and vaccine efficacy of murine dendritic cells simultaneously expressing melanoma-associated antigen and interleukin-12. Cancer Gene The

88.Salgado CD, Kilby JM. Retroviruses and other latent viruses: the deadliest of pathogens are not necessarily the best candidates for bioterrorism. Journal of the South Carolina Medical Association. 2009;105:104-106.

89.Jacome A, Navarro S, Rio P, Yanez RM, Gonzalez-Murillo A, Lozano ML, et al. Lentiviral-mediated genetic correction of hematopoietic and mesenchymal progenitor cells from Fanconi anemia patients. Molecular therapy : the journal of the

90.Yasutsugu Suzuki and Youichi Suzuki (July 20th 2011). Gene Regulatable Lentiviral Vector System, Viral Gene Therapy Ke Xu, IntechOpen, DOI: 10.5772/18155.

91.Borsotti C, Borroni E, Follenzi A. Lentiviral vector interactions with the host cell. Curr Opin Virol. 2016;21:102-108.